Before the 1979 Conservative government we had a plethora of council housing - owned by local authorities and leased to those who could not afford to buy their own homes. Then came along the Thatcher government and introduced the Right to Buy scheme, with enticements and discounts to encourage tenants to buy the house they had previously been renting. OK, you might think, so what, they will build more to replace them... but they didn't, and therein lies the problem!

The council houses that have been sold off were not replaced. The funds that their sale brought into local authorities which a sensible person might think should have been reinvested in housing were not allowed to be. Councils could not build more houses. This is a huge part of the reason for the housing crisis, it's why families are struggling in sub-standard expensive private rentals, or staying with relatives, and it's not good enough!

A bit of housing history...

Let's look at the origins of council housing as given on the Parliament.uk website:

In 2016 a further change occurred, when the Housing and Planning Act 2016 extended the Right to Buy to housing association tenants. This potentially affected an additional 1.3 million households without addressing either the net housing shortage or the difficulties in building new homes faced by local authorities and housing associations.

The fact verification website fullfact.org states:

George Clarke's website states:

If you would like to add your name to his campaign petition please do!

Let's look at the origins of council housing as given on the Parliament.uk website:

The end of the First World War in 1918 created a huge demand for working-class housing in towns throughout Britain. In 1919, Parliament passed the ambitious Housing Act which promised government subsidies to help finance the construction of 500,000 houses within three years. As the economy rapidly weakened in the early 1920s, however, funding had to be cut, and only 213,000 homes were completed under the Act’s provisions.

The 1919 Act - often known as the ‘Addison Act’ after its author, Dr Christopher Addison, the Minister of Health - was nevertheless a highly significant step forward in housing provision. It made housing a national responsibility, and local authorities were given the task of developing new housing and rented accommodation where it was needed by working people.

Further Acts during the 1920s extended the duty of local councils to make housing available as a social service. The Housing Act of 1924 gave substantial grants to local authorities in response to the acute housing shortages of these years. A fresh Housing Act of 1930 obliged local councils to clear all remaining slum housing, and provided further subsidies to re-house inhabitants. This single Act led to the clearance of more slums than at any time previously, and the building of 700,000 new homes.

Under the provisions of the inter-war Housing Acts local councils built a total of 1.1 million homes.

Think of that, 1.1 million homes built by local councils between 1919 and 1939, which equated to 55,000 houses per year.

Then came WW2 and the huge destruction of housing in many cities and ports across the country. The University of the West of England (Bristol)'s website on Domestic Architecture 1700 to 1960 explains what happened next:

At the end of the war, slums remained a problem in many large towns and cities and through enemy action 475,000 houses had been destroyed or made uninhabitable. In many towns and cities, temporary accommodation was provided by pre-fabricated houses. Altogether 156,000 prefabs were assembled using innovative materials such as steel and aluminium and proved a successful and popular house type. Although many well outlived their life expectancy, pre-fabs were only ever intended as a temporary measure and for the new post-war government the provision of new council housing was a top priority. Local authority house building resumed in 1946 and of the 2.5 million new houses and flats built up to 1957, 75% were local authority owned.

So, another 2.5 million houses and flats were built between 1945 and 1957 which equates to an average of more than 200,000 new homes per year.

Even in the late 1950s there were still houses available to rent privately, but the growth of council housing estates created new communities in towns, cities and villages across the UK and some of the older rental stock was sold off at low prices in many places, e.g. Radcliffe in Lancashire, where my late parents bought their 2-up, 2-down terraced cottage for £500 from the Wilton Estate. It had been realised that decent safe modern homes were needed by families and councils built them.

How did it all go wrong?

In 1979 the Conservatives won the General Election and one of the key note policies of the new government under PM Margaret Thatcher was the Right to Buy scheme:

After Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister in May 1979, the legislation to implement the Right to Buy was passed in the Housing Act 1980. Michael Heseltine, in his role as Secretary of State for the Environment, was in charge of implementing the legislation. Some 6,000,000 people were affected; about one in three actually purchased their housing unit.This meant that some 1.8 million council homes have been sold to tenants at a discount between the 3rd October 1980 and the end of 2015. For much of the time of those sales councils were not allowed to use the funds received from the sales to build new houses. It is only relatively recently that councils seem once again to be allowed to build houses, although most of these have been in conjunction with a housing association so are more properly social housing not council housing, as they are not managed by the councils themselves.

In 2016 a further change occurred, when the Housing and Planning Act 2016 extended the Right to Buy to housing association tenants. This potentially affected an additional 1.3 million households without addressing either the net housing shortage or the difficulties in building new homes faced by local authorities and housing associations.

The fact verification website fullfact.org states:

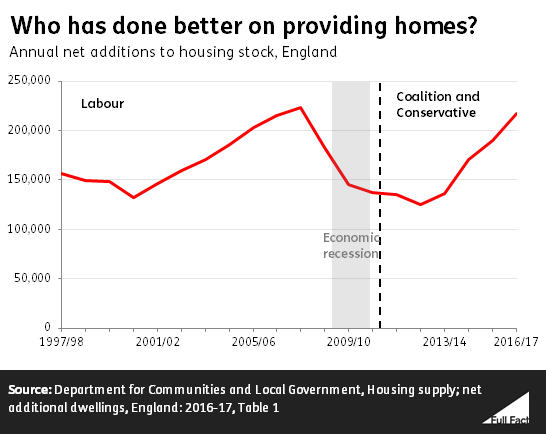

Taking a long view, house building has been mostly decreasing since the 1960s. The early years of this decade saw house building at its lowest peacetime level since the 1920s.

No recent government has seen enough homes built to keep up with demand.

In 2014 Dr Alan Holmans, a housing expert at the University of Cambridge, produced new estimates of the housing gap. They were based on 2011 data but took housing conversions, second homes and vacancies into account.

His analysis suggests that we need to build about 170,000 additional private sector houses and 75,000 social sector houses each year—in total, an extra 240,000-250,000 houses each year, excluding any reductions in the existing housing stock.So how many have been built and under which governments?

The graph doesn't give figures beyond 2016/17 but in November 2018 the charity Shelter stated:

At least 320,000 people are homeless in Britain, according to research by the housing charity Shelter.

This amounts to a year-on-year increase of 13,000, a 4% rise, despite government pledges to tackle the crisis. The estimate suggests that nationally one in 200 people are homeless.To provide homes for all the homeless will take political will, something which seems sadly lacking in this Tory government.

George Clarke's website states:

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the creation of council housing. But instead of being able to proudly celebrate its success we are sadly, firmly in the midst of a housing crisis.

Our country has not been building enough new council houses to meet demand. And since the 1980s, millions of council houses have been sold off through the Right to Buy without being replaced.

The result – more than 1 million people are on council house waiting lists today.Is it any wonder that George Clarke is calling for 100,000 new council houses to be built every year for the next 30 years?

If you would like to add your name to his campaign petition please do!